Power and water supplies are generally reliable

The key aim of the Program is to provide power, water and wastewater systems to eligible communities. In order to maintain reliable services, outages need to be fixed quickly and assets need to be maintained. The Program’s target is that at least 75 per cent of power outages, water outages and sewage overflows will be responded to within 24 hours of the Service Provider being notified.

On average, there were two power and two water service outages in each community each year over the past three years (Figure 2). These results meet the Program targets and are similar to service levels provided by town and city utilities.

Service Providers acted on around 90 per cent of service outages within the target of 24 hours, although distance and remoteness at times make it hard to repair assets quickly (Figure 3). However, individual performance varied. For example, the Pilbara addressed service disruptions within the 24 hour timeframe around 80 per cent of the time, compared to 95 per cent of the time in the Goldfields and close to 100 per cent of the time in the Kimberley. We found no evidence of recurrent outages seriously affecting individual communities.

Until this year, Housing only recorded outage length in terms of less than or more than 24 hours. This meant it did not know when longer outages may have significantly affected communities. There were five power outages of more than 24 hours in 2013‑14.

Service Providers can fix some interruptions to both power and water without travelling to the community using remote access and controls in place for some assets and systems. Housing plans to roll out similar access and controls to all assets, prioritised according to need, but timing will depend on funds being available.

Where remote monitoring is unavailable or cannot fix the problem, Service Providers can also employ community members to carry out some of this work. Fourteen communities have trained Essential Service Officers in place to carry out unplanned or emergency repairs. There are also Essential Service Technicians in four communities, who can carry out planned maintenance.

Water quality in communities often fails to meet Australian health standards

The Program aims to comply with the Australian Drinking Water Guidelines (the Guidelines) that set microbiological, chemical and aesthetic standards for drinking water. In the two years to June 2014, the water supply at four out of five communities failed to meet microbiological quality standards at least once because either Escherichia coli (E.coli) or Naegleria was detected. These microbes can cause life-threatening illnesses and present the main risk to human health from drinking water. Some communities had repeated cases of Naegleria and E. coli, as well as unsafe levels of the chemical contaminants nitrates and uranium.

The Guidelines are the minimum standards for drinking water quality set by the National Health and Medical Research Council in collaboration with the Natural Resource Management Ministerial Council. The Guidelines recommend weekly sampling for communities under 1 000 people, but recognise the need to consider the logistics of collecting the samples, the nature of the water supply, and the treatment system in place.

Service Providers sample community supplies monthly for microbiological testing against these Guidelines. Housing informed us that weekly testing would cost substantially more than the $1.8 million per year it currently costs. The impact is that water quality issues might exist for up to a month before being identified. Testing for physical, chemical and aesthetic quality is six-monthly.

When chemical and microbiological test results do not meet the Guidelines, communities are notified by telephone, fax and email and advisory notices are placed around the community. When tests fail, the Service Providers respond in various ways:

- increased sampling and testing

- supplying bottled drinking water

- providing new or upgraded infrastructure

- seeking new water sources

- blending existing water sources to reduce concentrations to acceptable limits.

Since July 2012, remediation costs following microbiological test failures have totalled nearly $600 000.

We did not look at aesthetic factors such as smell, taste and discolouration because they do not directly threaten health. However, Housing and some communities advised us that these factors deter some people from using safe water sources in favour of less safe but more palatable sources.

Eighty per cent of communities sometimes failed drinking water tests for Naegleria or E. coli

Over the two years to June 2014, at least one community failed a water quality test every month for either E. coli or Naegleria (Figure 4). In January 2014, twelve communities failed one or both tests. Sixty-eight communities had at least one test failure over the two years.

Data is not available to show how many people fell ill as a result of these failures because the small number of individuals affected does not show up in health statistics, but the risks are significant at a community level and well understood by stakeholders. By comparison, Health has reported no failures for E. coli or Naegleria at any test site in WA managed by Water Corporation since at least 2008.

Over the two years to June 2014, thirty-nine communities had two or more failures, while 29 had three or more. In that period, Koorabye has failed 11 times, making tap water unsafe for much of that time. However, we note that the Program installed a chlorination unit at Koorabye in July 2014, making the water much safer to drink since then. We also note that no Pilbara communities failed E.coli tests in the 12 months to April 2015.

The four communities with the worst microbiological performance were among 33 that still had UV water treatment systems at June 2014. These systems are ineffective if the power fails or the water is not clear. Housing is replacing UV systems with more effective chlorination systems as funds become available.

One in five communities exceeded safe levels for nitrates or uranium

The most significant chemical issues for water quality come from nitrates and uranium, which occur naturally and are common in the Goldfields and Pilbara. Excessive nitrates in the diet reduce blood’s ability to carry oxygen. In infants, this can cause the potentially life-threatening Blue Baby Syndrome, where the skin takes on a bluish colour and the child has trouble breathing. Housing provides bottled water for infants under three months in communities with high nitrates. Long term solutions would likely include asset replacements or upgrades or finding new water sources, or a combination of these.

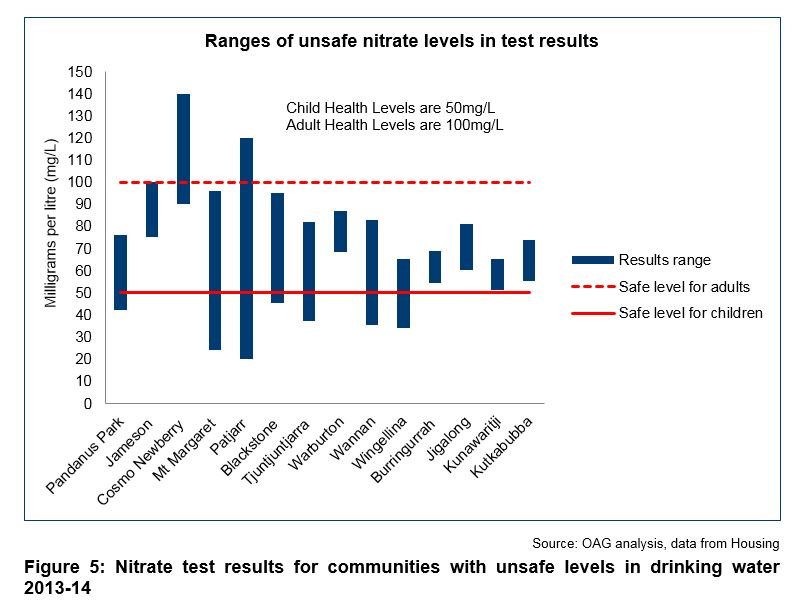

In 2013-14, fourteen of 84 communities in the Program recorded nitrates above the safe health level for bottle-fed babies under three months. Two communities had readings above the standard for adults (Figure 5).

Monitoring for uranium in water supplies is happening at five communities where uranium levels are high. Uranium leaches naturally from soils, rocks and natural deposits, but is also released through mining processes. It is carcinogenic and high concentrations can cause kidney inflammation.

In the last two years, three communities have exceeded the safe limit of 0.017 mg/L about half the time, while Tjuntjuntjara in the Goldfields failed 18 out of 22 tests. Some of these results were up to double the safe level. To manage this, water from several bores is blended to achieve acceptable uranium levels. Since October 2014, there has been fortnightly testing at Tjuntjuntjara to better understand the raw water supply.

Inadequate testing of wastewater systems is creating health risks

Prolonged breakdown of wastewater systems can reduce the effectiveness of sewage processing. Leaks and overflows also increase the risks of mosquito-borne disease. Service Providers are required to inspect all wastewater and sewer systems monthly during planned maintenance activities and to report on their condition and operation to Housing. They are also required to test sewer ponds twice yearly for microbes and chemicals and report the results to the Department of Health and to Housing via the Program Manager.

We found that Service Providers’ testing of sewer ponds has been irregular or not included all ponds. The lack of testing means that Housing does not always know how well the evaporation ponds are working, and this poses risks to community health. Of 39 communities in the Program with sewer ponds, none had all the testing they required in the two years to June 2014. However, all Service Providers are now sampling and testing according to their contracts.

Blockages causing overflows are a common problem in communities. Between July 2012 and June 2014, nineteen communities reported 37 wastewater overflows. Overflows risk exposing community members to untreated sewage. The Kimberley community of Mowanjum experienced eight sewer system overflows in 11 months. The lack of septic tanks had allowed solids to enter the main sewer and block it. Adding a primary pit and grinder pumps solved the problem in late March 2015.